Budget 2024: Plugging the R15 billion tax hole

Johannesburg, 16 February 2024 – In the 2023 Medium Term Budget Policy Statement, the Minister of Finance already identified that tax collections would not be as robust as he had projected in February 2023. A downward adjustment of R53 billion was then made to the 2024/2025 expected revenue collections, though tax revenues were expected to increase to R2,1 trillion over the 2023-2026 medium term. In addition, the Minister noted that he would also have to raise additional revenue to partially plug this hole, and a need for a further R15 billion in taxes was projected for the 2024/2025 fiscal year.

So where will this R15 billion come from, asks Pieter Faber, Senior Executive: Tax at the South African Institute of Chartered Accountants (SAICA).

The Minister has conceded that South Africans are some of the most highly taxed taxpayers in the world, we have a relatively small income tax base and the previous tax increases, such as the VAT increase, did not deliver the expected additional revenue given the first two factors.

Would we need another VAT increase, an increase in personal income taxes or a revision of the corporate income tax rate to 28%? While R15 billion is not a large amount in comparison to a R1,9 trillion budget, its impact could be significant for ordinary people. So how could this R15 billion potentially be raised?

The first point of call is doing away with bracket creep or inflationary adjustments to tax brackets. It was estimated in the 2023 Budget that if a full inflationary adjustment is made, R15,7 billion in revenue is forfeited. The 2023 Budget however saw a partial inflationary adjustment to personal income tax brackets, mostly at the lower end, providing R2,2 billion in bracket creep or inflation relief. Providing no relief in 2024 could yield a similar amount.

Another option is not providing inflationary relief for medical tax credits which, based on previous years, could yield another R1-2 billion. This would be similar to the stance taken in the 2019 Budget when the current administration took over, and no inflationary increases were provided for medical tax credits or the personal income tax brackets.

Compare this to 2009 when R13,6 billion in personal tax relief was provided, and it is clear that this measure has already been eroded over the years. The government has in fact over the last few years already started taxing taxpayers on inflation, reducing their actual spending power and contributions to the economy.

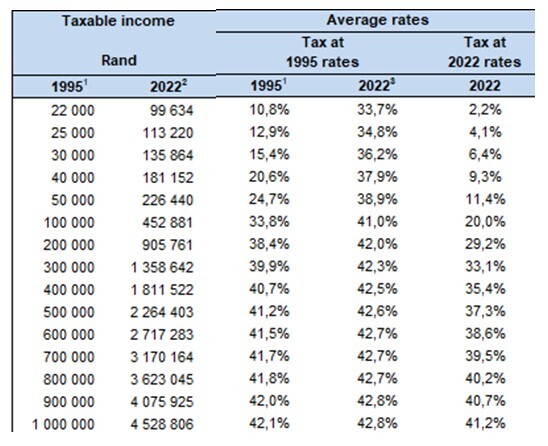

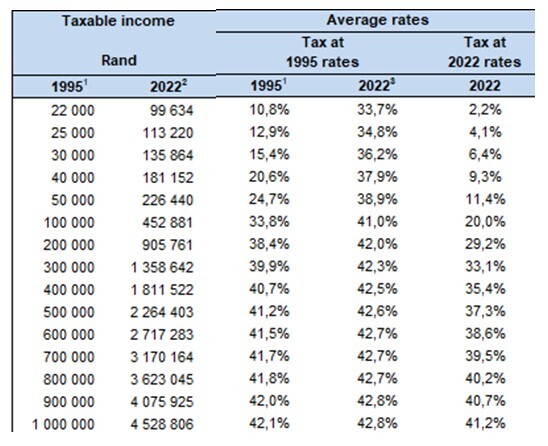

This is well demonstrated by the SARS Tax Statistics:

In essence, a person earning R100 000 in 1995 would, due to tax relief provided over the years, pay tax at a rate of about 21%, or less than half the tax payable today on an equivalent amount (R452 000). However, a top earner earning R1 million in 1995 would pay nearly the same amount of tax, indicating that nearly no tax relief has been provided to this tier over the last 29 years.

Further shaves could include the interest and dividend exemptions. Interest and dividend receipts have stagnated over the years and are declining in line with South Africans' general decline in savings rates; so very little, if any, additional revenue will be received from keeping the exemption thresholds the same.

An interesting windfall may be a decline in the abuse of the Employment Tax Incentive after SARS’ enforcement action in 2023. This incentive nearly doubled from 2020-2021 (R4-7 billion). If, as suspected, nearly half of these claims are abusive, another R3 billion could be “won”.

After shaving off here and there, we are still short of the R15 billion. So, let’s look at other options, including tax increases.

About 75% of all personal income tax, roughly R335 billion, is paid by the 1,1 million taxpayers (19% of assessed taxpayers) earning R500 000 and above. So, to get the full R15 billion would require a 4,5% increase in taxes paid by this demographic. If this burden was equally distributed amongst these persons, that would be an additional R5 991 annual tax for a person earning R500 000 a year. For a person earning R1 500 000 a year, that would be R25 961 per annum, or nearly R2 000 per month in additional tax. However, given the historic trend, this will be an unequal distribution, with the R500 000 salary band paying less than that and the R1,5 million band paying even more.

A more impactful measure would be doing away with medical tax credits in anticipation of National Health Insurance (‘NHI’) as mentioned in the State of the Nation Address (‘SONA’) 2024. This would release about R36 billion, more than twice what the Minister wanted. This will largely impact the 9,7 million medical aid members and dependents, which based on the current medical tax credits, amounts to R974 per month for a family of three. It may however be that this money is earmarked as seed capital for the “phased” NHI implementation, and therefore not part of this plan, resulting in a “double whammy” for this small upper taxpayer pool looking at losing medical credits and paying higher taxes.

The latter might seem unlikely, but given the election promises of maintaining the Social Relief Grant (‘SRG’), implementation of NHI, on top of more records of State-Owned Enterprise (‘SOE’) losses (like Eskom R7,5 billion, South African Airways (‘SAA’) R750 million, South African Post Office (SAPO) R0,5 billion) and debt realisations, like Transnet’s R47 billion debt that it can’t pay, anything is possible. In addition to this, tax collections may be even worse than projected in November 2023, and spending significantly higher given the unbudgeted wage increases, etc. This last “double whammy” scenario may very quickly become more likely than not and an already financially stretched taxpayer community is very likely in for more pain in 2024.

SAICA Media Contacts

Kgauhelo Dioka, ***@saica.co.za

Project Manager: Communications

SAICA Brand Division

Renette Human, ***@saica.co.za

Project Director: Communications

SAICA Brand Division

Johannesburg, 16 February 2024 – In the 2023 Medium Term Budget Policy Statement, the Minister of Finance already identified that tax collections would not be as robust as he had projected in February 2023. A downward adjustment of R53 billion was then made to the 2024/2025 expected revenue collections, though tax revenues were expected to increase to R2,1 trillion over the 2023-2026 medium term. In addition, the Minister noted that he would also have to raise additional revenue to partially plug this hole, and a need for a further R15 billion in taxes was projected for the 2024/2025 fiscal year.

So where will this R15 billion come from, asks Pieter Faber, Senior Executive: Tax at the South African Institute of Chartered Accountants (SAICA).

The Minister has conceded that South Africans are some of the most highly taxed taxpayers in the world, we have a relatively small income tax base and the previous tax increases, such as the VAT increase, did not deliver the expected additional revenue given the first two factors.

Would we need another VAT increase, an increase in personal income taxes or a revision of the corporate income tax rate to 28%? While R15 billion is not a large amount in comparison to a R1,9 trillion budget, its impact could be significant for ordinary people. So how could this R15 billion potentially be raised?

The first point of call is doing away with bracket creep or inflationary adjustments to tax brackets. It was estimated in the 2023 Budget that if a full inflationary adjustment is made, R15,7 billion in revenue is forfeited. The 2023 Budget however saw a partial inflationary adjustment to personal income tax brackets, mostly at the lower end, providing R2,2 billion in bracket creep or inflation relief. Providing no relief in 2024 could yield a similar amount.

Another option is not providing inflationary relief for medical tax credits which, based on previous years, could yield another R1-2 billion. This would be similar to the stance taken in the 2019 Budget when the current administration took over, and no inflationary increases were provided for medical tax credits or the personal income tax brackets.

Compare this to 2009 when R13,6 billion in personal tax relief was provided, and it is clear that this measure has already been eroded over the years. The government has in fact over the last few years already started taxing taxpayers on inflation, reducing their actual spending power and contributions to the economy.

This is well demonstrated by the SARS Tax Statistics:

In essence, a person earning R100 000 in 1995 would, due to tax relief provided over the years, pay tax at a rate of about 21%, or less than half the tax payable today on an equivalent amount (R452 000). However, a top earner earning R1 million in 1995 would pay nearly the same amount of tax, indicating that nearly no tax relief has been provided to this tier over the last 29 years.

Further shaves could include the interest and dividend exemptions. Interest and dividend receipts have stagnated over the years and are declining in line with South Africans' general decline in savings rates; so very little, if any, additional revenue will be received from keeping the exemption thresholds the same.

An interesting windfall may be a decline in the abuse of the Employment Tax Incentive after SARS’ enforcement action in 2023. This incentive nearly doubled from 2020-2021 (R4-7 billion). If, as suspected, nearly half of these claims are abusive, another R3 billion could be “won”.

After shaving off here and there, we are still short of the R15 billion. So, let’s look at other options, including tax increases.

About 75% of all personal income tax, roughly R335 billion, is paid by the 1,1 million taxpayers (19% of assessed taxpayers) earning R500 000 and above. So, to get the full R15 billion would require a 4,5% increase in taxes paid by this demographic. If this burden was equally distributed amongst these persons, that would be an additional R5 991 annual tax for a person earning R500 000 a year. For a person earning R1 500 000 a year, that would be R25 961 per annum, or nearly R2 000 per month in additional tax. However, given the historic trend, this will be an unequal distribution, with the R500 000 salary band paying less than that and the R1,5 million band paying even more.

A more impactful measure would be doing away with medical tax credits in anticipation of National Health Insurance (‘NHI’) as mentioned in the State of the Nation Address (‘SONA’) 2024. This would release about R36 billion, more than twice what the Minister wanted. This will largely impact the 9,7 million medical aid members and dependents, which based on the current medical tax credits, amounts to R974 per month for a family of three. It may however be that this money is earmarked as seed capital for the “phased” NHI implementation, and therefore not part of this plan, resulting in a “double whammy” for this small upper taxpayer pool looking at losing medical credits and paying higher taxes.

The latter might seem unlikely, but given the election promises of maintaining the Social Relief Grant (‘SRG’), implementation of NHI, on top of more records of State-Owned Enterprise (‘SOE’) losses (like Eskom R7,5 billion, South African Airways (‘SAA’) R750 million, South African Post Office (SAPO) R0,5 billion) and debt realisations, like Transnet’s R47 billion debt that it can’t pay, anything is possible. In addition to this, tax collections may be even worse than projected in November 2023, and spending significantly higher given the unbudgeted wage increases, etc. This last “double whammy” scenario may very quickly become more likely than not and an already financially stretched taxpayer community is very likely in for more pain in 2024.

SAICA Media Contacts

Kgauhelo Dioka, ***@saica.co.za

Project Manager: Communications

SAICA Brand Division

Renette Human, ***@saica.co.za

Project Director: Communications

SAICA Brand Division